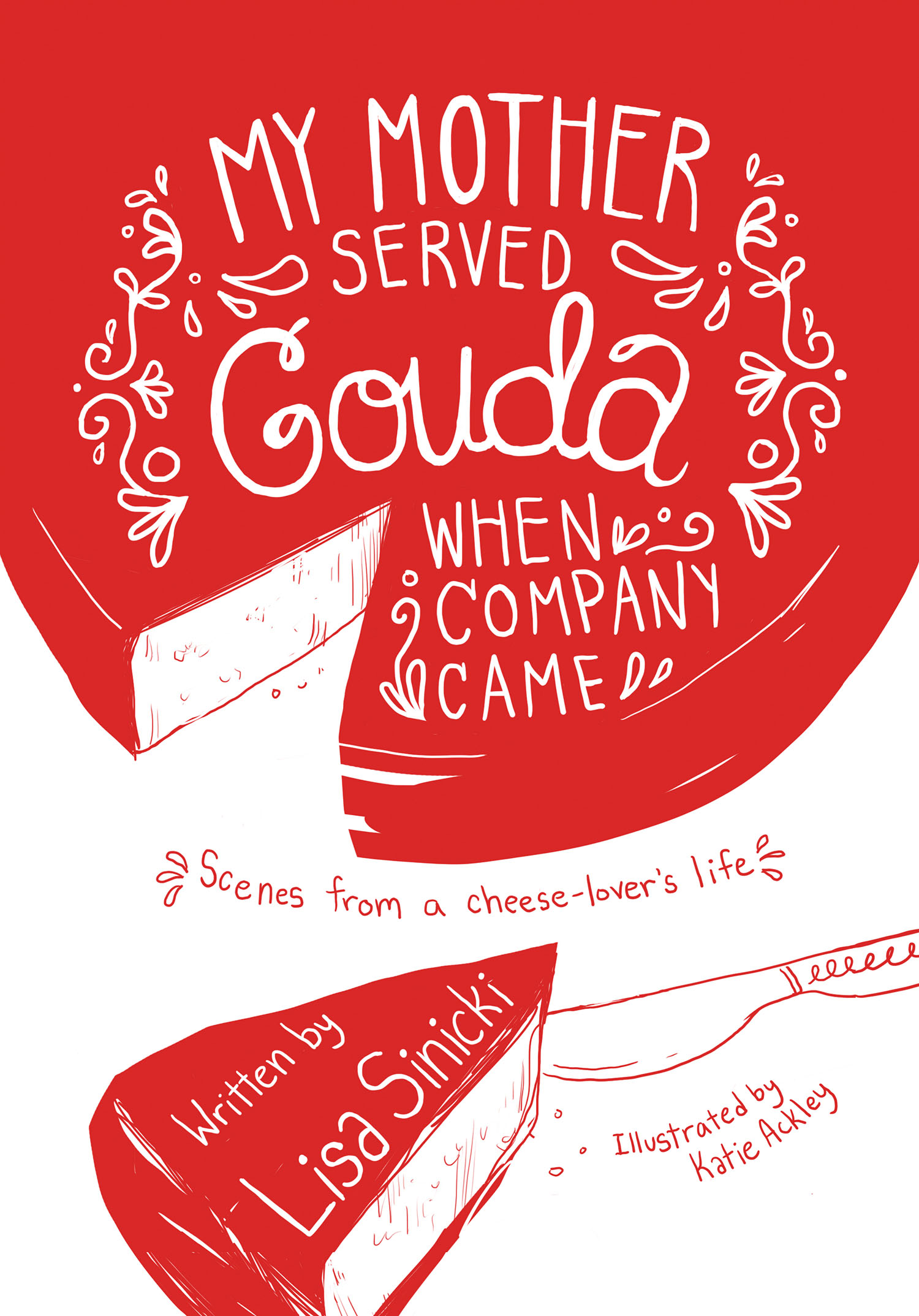

Sample chapter from Lisa Sinicki's mini-memoir:

My Mother Served Gouda When Company Came

Family Bonding Cheese

American. That’s what I remember from my childhood. American was what I was—and American was what I ate. My country, my nationality, my sustenance, my cheese.

In the late-1960s, I looked forward to the crisp grilled cheese sandwiches my parents made for Sunday lunch; it was so much better than the meat-plus-starch-plus-frozen-vegetable meals we usually ate.

My little brother, Ric, and I watched as Mom took the ingredients out of the refrigerator. Then Dad prepared the grilled cheeses for grilling on the electric sandwich press: one single, perfect square of American cheese sandwiched between two slices of Wonder Bread—and spread with margarine. It was a party of cheese, bread, and margarine, and it was as special to me then, as its ingredients are questionable to me now.

Dad handled the slices of Wonder Bread carefully. It required skill to spread the margarine without tearing the bread’s spongy surface. I grinned. It was a treat to have him participate in family activities. As a typical suburban household, we were aware of hippie culture, supported civil rights, and wore bell-bottoms. But inside our home, we acted like it was still the 1950s. We lived in Middletown, New Jersey, a standard “two” family: two parents, two cars—and two children spaced two years apart. My parents operated under a traditional 1960s husband and wife agreement: He, the man, earned our living, and she, the woman, took care of the house and kids. By the terms of the agreement, Dad rarely participated in household duties—except for “man jobs” like painting, appliance repair, grilling meat, and yard work. Grilled cheese-making was a special exception to the rules. There was no man’s job or woman’s work in grilled cheese—just family and cheesy goodness. Maybe that’s what made it taste awesome.

I wanted to help, so Dad let me ready the cheese. Back then, American cheese came in a block—roughly four inches-by-four inches at the base, two inches high, and as peachy-orange as a bridesmaid’s dress. It had been pre-sliced, like a loaf of bread, with the slices then stacked back together. I peeled the top square off of the block very carefully so it wouldn’t tear. American cheese’s power was tied to the uniformity of its slices—there was something important about the exact sameness of every slice that I wanted to preserve.

After the bread was cheesed and margarined, Dad tossed the sandwiches onto the press—a contraption that looked like a chrome toaster split in two and laid on its side, a pair of rickety springs connecting top to bottom. The margarine seared, ssshhhhh, on the hot metal plates. It was a special treat when the cheese dribbled out from between the bread and touched the grill, producing a brown and crispy cheese tail.

Dad made our sandwiches, one for Ric and I to split, and a second one for Mom. Mom hovered while Dad cooked to ensure he added a slice of tomato to her sandwich. She got the tomato because she was the only one in our family who liked vegetables. She watched over his shoulder because that was her—always inspecting to make sure things were done exactly the way she wanted them done.

For the second batch, Dad made his own sandwich and an additional sandwich that Mom cut into quarters. We divvied up the four bonus pieces at the table: I took one, Ric took one, and Dad ate the remaining two. Then we all sat and ate.

Sometimes I squished my sandwich and ate the cheese that dribbled out around the sides first. Other times, I bit around the outside, to create a crust-less square. I wanted my sandwich—and my time with my family—to last forever.